How Takoradi Helped Win World War II

For this interesting post that I shared on 13th November 2018, my attention has just been drawn by Kwei Quartey, the Foreign Policy In Focus columnist, as the author who wrote the piece. I had indicated in the article that there was a source for the story, “How West Africa Helped Win World War II”. I never intended nor hid the fact that the story had a source that was not Kenneth Ashigbey. Now I have the link to the original source of the story. That has been added to this piece. All credits go to Kwei Quartey, if there are any errors in the reproduction, that would be my responsibility. Enjoy how Takoradi helped win the Second World War. I pray we have other researchers out there looking into other contributions of Africa to global events.

The story of Africa’s contribution to the world war is terribly not told. Even we as Africans do not know what we contributed to these wars. Lets all begin to learn and tell our children what they need to know. Till Africans begin to tell our stories, the story of our escapades will favour others.

In June 1940, when France fell to the German invasion, Italy seized the moment to attack British positions in Egypt, Kenya, and Sudan. By the end of March 1941, German Major-General Erwin Rommel’s mechanized troops had driven the British out of Libya and back into Egypt. In late spring, German and Italian aircraft were pummeling Britain’s sea stations in the Mediterranean, making it difficult if not impossible for supply ships to reach British forces in the Middle East. The remaining sea route by which to deliver supplies to Egypt was via Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, but that was a protracted journey of three to four months, a luxury of time that Britain simply did not have.

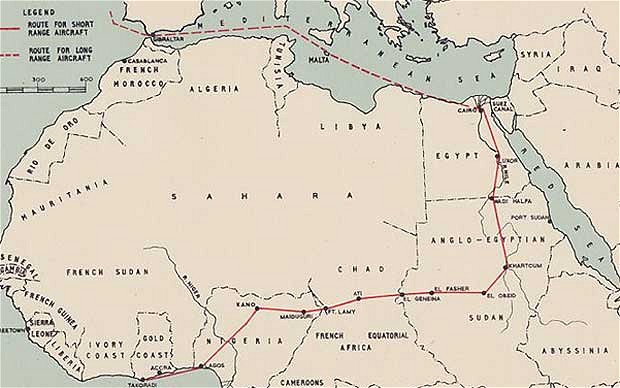

In desperation, Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his military advisers turned to an underdeveloped, 3,700-mile air route from Takoradi in the British colony of the Gold Coast (now Ghana) to Cairo, Egypt.

Takoradi’s Major Role

As the starting point of the Allied trans-African supply line to Egypt that became officially known as the West African Reinforcement Route (WARR), Takoradi became one of the most important bases for Britain’s Royal Air Force (RAF). On September 5, 1940, the first shipment of a dozen Hurricane and Blenheim aircraft fighters in large wooden crates arrived at Takoradi by boat from the United Kingdom, and like many more consignments to come, they were unpacked and then assembled locally to be made airworthy for the flight to Cairo. The six-day journey was undertaken in stages with several rest and refuelling stops that included Lagos, Nigeria; Khartoum, Sudan; and Luxor, Egypt. Nelson Gilboe, a Hurricane pilot, describes the Takoradi assembly plant as cut out of the dense forest with monkeys playing in nearby trees. (Simian residents of modern-day Takoradi still frolic in the trees of the Monkey Hill sanctuary.)

The first delivery flight to Cairo left Takoradi on September 20, 1940. Like the flights that were to follow, it was a journey plagued by problems. In the Sahara Desert portion of the route, and took a severe toll on the aircraft engines. There was no map of the route, and many pilots used ominously burned-out aircraft on the ground as their guide.

The first delivery flight to Cairo left Takoradi on September 20, 1940. Like the flights that were to follow, it was a journey plagued by problems. In the Sahara Desert portion of the route, and took a severe toll on the aircraft engines. There was no map of the route, and many pilots used ominously burned-out aircraft on the ground as their guide.

In spite of these challenges, between August 1940 and June 1943, over 4,500 British Blenheims, Hurricanes, and Spitfires were assembled at Takoradi and ferried to the Middle East. Between January 1942 and the end of the operation in October 1944, 2,200 Baltimores, Dakotas, and Hudsons arrived from the United States (via the American base at Natal, Brazil, and a mid-Atlantic stop on Ascension Island), and virtually all of them were ferried in a similar fashion. There were other final destinations via the Takoradi Route, including India.

Empire and Commonwealth

The term “Allies” is invariably used to refer to the wartime partnership between Britain and the United States, but it was the British Empire that was plunged into war from the very beginning in September 1939, a good two years before the United States took on a combatant role. In her book The British Empire and the Second World War, Ashley Jackson points out that notwithstanding the Eurocentric manner in which World War II is often remembered, the British and many ordinary people around the world viewed the war as an imperial struggle. The idealized image of Britain standing alone after the fall of France is a parochial and inaccurate one. Over a span of centuries, Britain’s imperialism had created an empire comprising dominions, colonies, and protectorates. Whom and where the British fought was largely determined by its empire. After all, there would hardly have been anything for Italy or Japan to quarrel about had it not been for two centuries of British overseas expansion right under their noses.

Churchill and many British government ministers at the time had had direct experience with the Empire and its people, and it was inevitable that the crafting of the war involved the marshalling of Empire and Commonwealth forces. African kings like the Asantehene of the Gold Coast became indispensable resources in this effort because they were able to mobilize their subjects for all manner of projects, whether it was to join the imperial army, help assemble Hurricanes, or construct airfields, harbours, and roads. In the first few years of the war, the RAF recruited 10,000 West Africans for ground duties in the British West Africa colonies of the Gold Coast, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and the Gambia. To be sure, British personnel, who were succumbing to West Africa’s punishing heat and enervating malarial attacks, needed support from an acclimatized populace in a region of the world sometimes called the “White Man’s Grave.”

Churchill and many British government ministers at the time had had direct experience with the Empire and its people, and it was inevitable that the crafting of the war involved the marshalling of Empire and Commonwealth forces. African kings like the Asantehene of the Gold Coast became indispensable resources in this effort because they were able to mobilize their subjects for all manner of projects, whether it was to join the imperial army, help assemble Hurricanes, or construct airfields, harbours, and roads. In the first few years of the war, the RAF recruited 10,000 West Africans for ground duties in the British West Africa colonies of the Gold Coast, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and the Gambia. To be sure, British personnel, who were succumbing to West Africa’s punishing heat and enervating malarial attacks, needed support from an acclimatized populace in a region of the world sometimes called the “White Man’s Grave.”

Beyond that, West African soldiers went to the battlefront itself. The 4th Gold Coast Infantry Brigade, which later became the 2nd West African Infantry Brigade, contributed 65,000 men to the 1944 Battle of Myohaung, which drove the Japanese out of Burma. Today, in testament to that history, the military section of Accra, Ghana’s capital, is called Burma Camp, and there is a Myohaung Barracks at Takoradi.

Resources and Location

The war brought about a greater demand for Africa’s raw materials. With the loss of Southeast Asia’s rubber to the Japanese, Nigeria became one of Britain’s most important sources of rubber. The Gold Coast’s bauxite, the raw material for aluminium, was critical to British aircraft production. It would be misleading to say, however, that these contributions were all made under blissful conditions. Britain’s ultimately failed attempts to increase tin mining in Nigeria involved forced labour under appalling conditions.

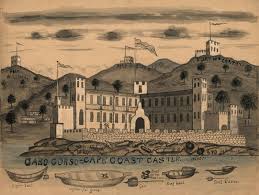

Apart from having the Takoradi air force base on its shores and the headquarters of the West Africa Command at Achimota College, which supplied the 200,000 total military men from the four West African British colonies, the Gold Coast was of strategic importance for another reason: it was bordered on all sides by potentially hostile French colonies that were under the Vichy Government. If the Gold Coast had fallen to the enemy, the West African Reinforcement Route would have come to an end.

The lesson is that the Second World War’s Eurocentric history must be widened to give sub-Saharan Africans and many other world peoples their due. In September 1940, clearly recognizing the critical importance of defending the skies over the Mediterranean, Winston Churchill observed, “The Navy can lose us the war, but only the Air Force can win it.” The contributions and cooperation of Africans along the Takoradi Route made the fulfilment of that principle possible and the defeat of the Axis forces a reality.

Source: How West Africa Helped Win World War II – https://www.huffpost.com/entry/west-africa-world-war-ii_b_1573810

This post has already been read 3005 times!

3 comments