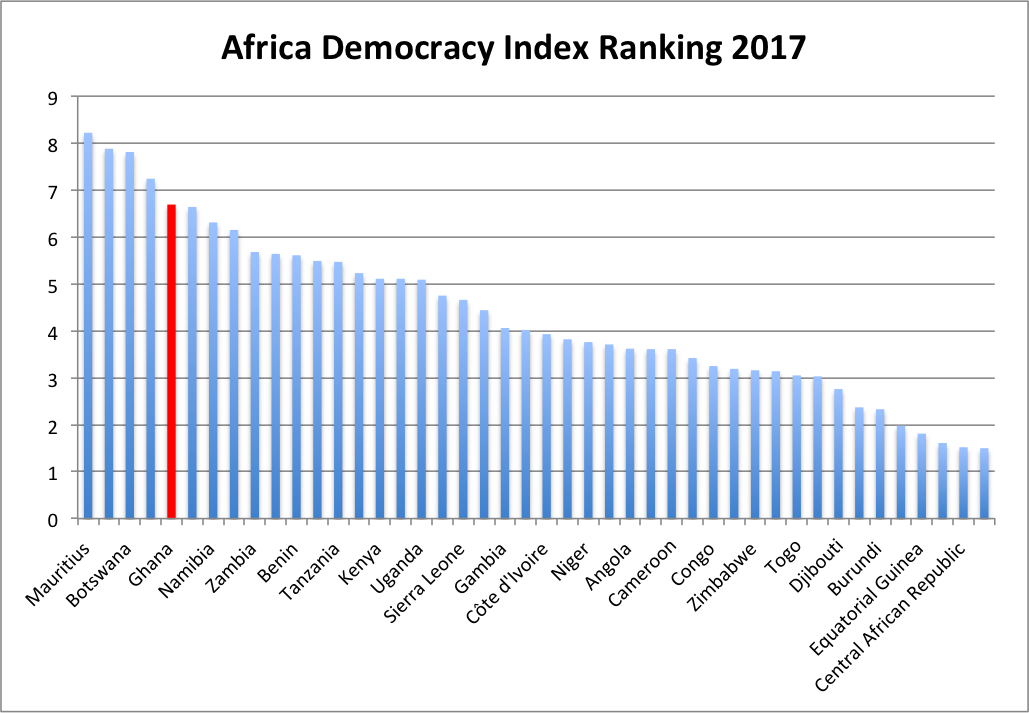

Ghana places 5th in Africa in EIU Democracy Index

Ghana placed 5th in the EIU Democracy Index ranking after Mauritius which is the only classified country classified as a Full democracy followed by Cape Verde, Botswana and South Africa who are all classified as Flawed democracies.

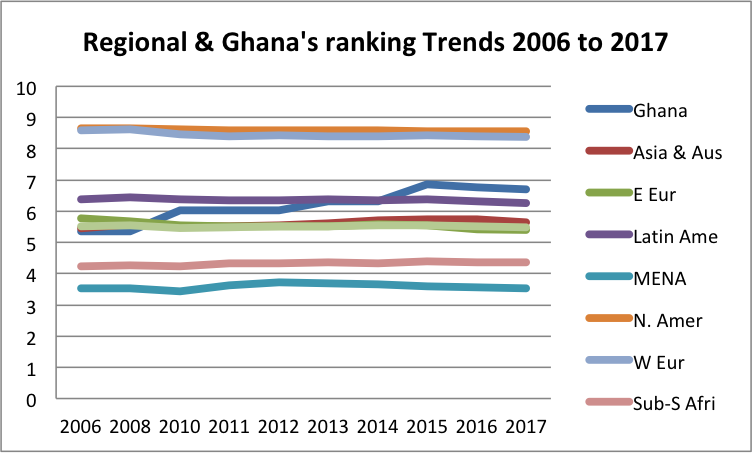

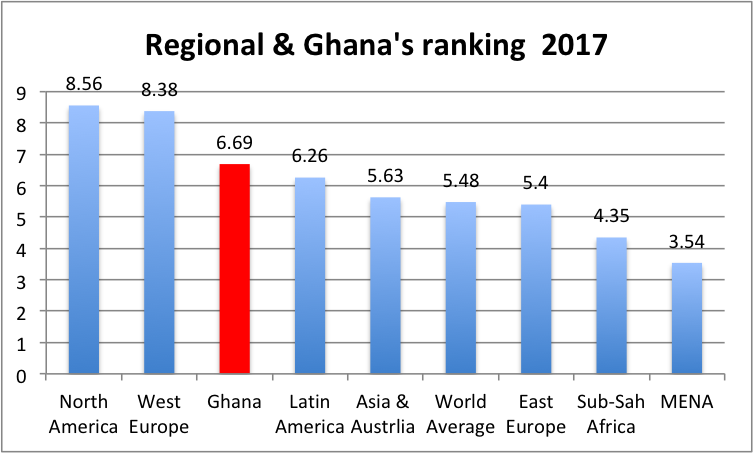

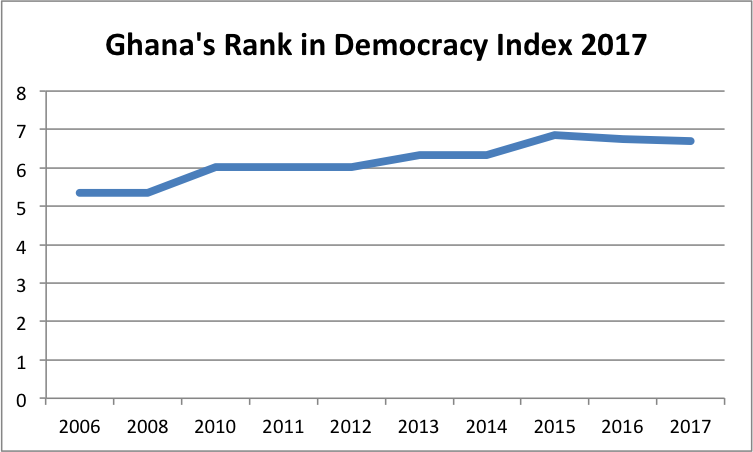

Reflecting the scant democratic progress made in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) in recent years, the region’s average score in the Democracy Index has remained relatively flat since 2011, but dipped again in 2017, to 4.35 (from 4.37 in 2016 and 4.38 in 2015). Political participation and political culture have improved over the past five years (albeit with a few notable exceptions), but this has been offset by deteriorating scores for civil liberties and the functioning of government.

Moreover, while elections have become commonplace across much of the region, the regional score for electoral processes has remained persistently low, reflecting a lack of genuine pluralism in most countries.

The relatively unchanged average headline score for the region masks a mixed picture, in which a few significant score increases in 2017 helped to offset a wider trend of deterioration across much of the continent. Only 11 countries out of the 44 recorded any improvement in their overall score, eight were unchanged, and so the majority, 25, suffered a deterioration in their democratic credentials.

There was one star performer, The Gambia, which was upgraded from being among the world’s most authoritarian regimes to being a “hybrid democracy”. The country’s score also rose by more than any other country in the entire 2017 index, and by a considerable margin.

There were significant changes in the category of electoral process in 2017; the average score for the region improved from 4.20 in 2016 to 4.31. However, some countries still face major challenges in this area.

Kenya and Liberia found their respective elections to be extremely testing periods, with first round results of presidential polls becoming mired in legal challenges and the threat of constitutional crisis. In both contests the prospect of an opposition figure achieving government was high (and eventually happened in Liberia), but the chances of a smooth electoral process were blighted by unclear, unestablished and unaccepted institutional mechanisms for dealing with electoral disputes.

The same was the case for The Gambia in a contested December 2016 presidential election, where the impasse was resolved only in early 2017 by external military intervention, not domestic institutions.

The only other category which registered an improved score in 2017 was political participation, with an increase from 4.26 to 4.32. Legislatures and cabinets have more women, populations turned out to vote in greater numbers in some elections, and electronic media are making it easier for people to follow politics. However, the picture is highly varied, with some populations finding their willingness to get involved in politics being obstructed.

Notably, demonstrations have become more difficult to attend in some places, with security forces taking a harder line on a growing number of protesters demanding political reform.

Tying in with this, the aggregate score for civil liberties also dropped in 2017, partly reflecting attacks on the media and on freedom of expression by governments. The score for the functioning of government remains the region’s weakest category, with an average score of 3.36, down from a score of 3.48 in 2016. There have long been glaring shortcomings in this area. In many countries accountability within government is weak or entirely absent; there are too few checks and balances on executives; corruption is endemic; the civil service is unskilled; and cronyism and patronage often trump efficiency in the eyes of policymakers. Confidence in government tends to be very low. No country except The Gambia improved in any aspect of the category, and several countries saw their scores for the functioning of government decline, either owing to a further lapse in accountability—as was the case in Mauritania, where the Senate and High Court were both disbanded—or, most commonly, worsening perceptions of corruption.

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2018

This post has already been read 1508 times!

1 comment